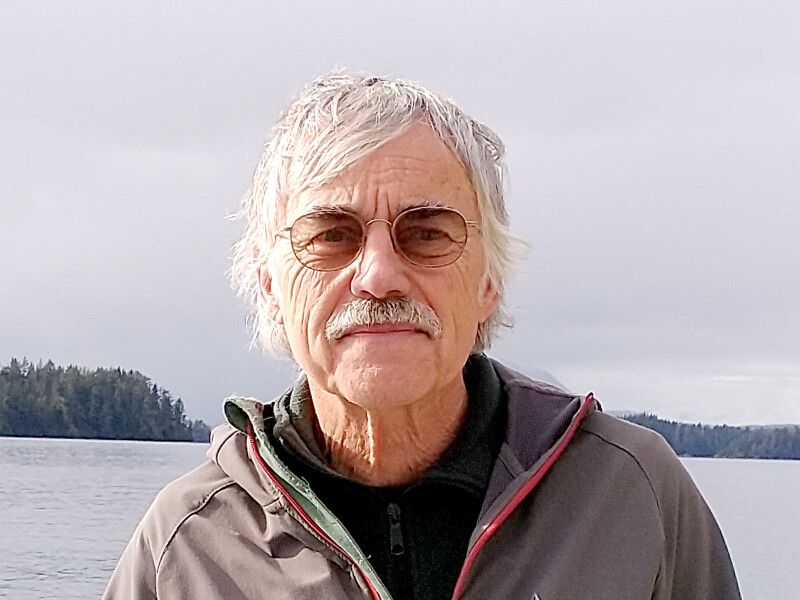

For anyone who believes in an orderly universe, Jerry Dzugan’s path from the South Side of Chicago schools to teaching fishing safety in Alaska could be an inspiration.

“When I came up here in 1978, I thought this was the kind of place I was looking for,” recalled Dzugan, who had been teaching in his hometown’s public schools since 1971. “Sitka was the place I wanted to move to.”

Dzugan, 73, stayed in the city until 1979, after that first trip had crystallized a plan. Over the next few years he built a new life in the north, working at fishing, surveying and construction — and with local emergency medical technicians.

His experience teaching led him into training first responders on land. Meanwhile the Alaska Marine Safety Education Association was organized in the early 1980s, seeded with grant money from NOAA as part of a Coast Guard outreach effort to improve fishing vessel safety.

Dzugan was recruited to AMSEA’s board of directors, and then as its executive director. Over the coming years, AMSEA grew to put 24,000 people through its training programs, and became a go-to model for fishing communities and advocates working to save lives off their own coasts.

That started when one of AMSEA’s safety instructor courses attracted someone from the NMFS observer office in Seattle, Dzugan recalled.

“I realized this is not just an Alaska thing,” he said. “This need exists everywhere.” Now AMSEA instructor training sessions routinely bring in students from other states, “and then people started coming from other countries,” said Dzugan.

When Congress worked on the 1988 Fishing Vessel Safety Act, Dzugan was tapped to be an adviser. With other advocates, he argued that mandatory safety training was needed. But there was heavy resistance in the industry, and Dzugan saw one reason why.

“I realized they were shooting it down because they had no access” to training programs and resources, he recalled. “We realized we need to bring everyone in.”

As AMSEA’s training programs and reputation grew, its influence spread to other coasts. After a disastrous January 1999 when four East Coast sea clamming vessels sank and took 10 lives in 13 days, the knowledge and experience of AMSEA was one of the first resources the industry and Coast Guard reached for.

The Coast Guard convened its Commercial Fishing Vessel Safety Task Force, drawing on government, industry and safety consultants from around the U.S. coasts. The Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, which pioneered the nation’s first individual transferable quota management system — in part to improve the surf clam fishery’s bad safety record in the 1980s — questioned if the system was safe enough.

A safety surge ensued: More training and emergency drills for fishermen, Coast Guard vessel safety examiners walking the docks, new emphasis on properly maintaining life rafts, survival suits and emergency position locating beacons.

The pandemic forced cutbacks in the instructor training schedule, but “when we’re up and running, we do about 100 classes a year,” said Dzugan. Average class size now is around five, down from 10, apparently a function of both saturation — some 18,000 in Alaska have been trained — and fewer people in the industry.

“In the 1980s and ’90s there were a lot of new crew coming up,” Dzugan noted. Now, with disruption from covid-19 and economic conditions, the industry is reporting problems recruiting, he added.

On the positive side, “there seems to be more of a safety culture among younger people,” said Dzugan. “They like it (training) because it’s hands-on and a group activity.”

During a National Transportation Safety Board online roundtable discussion on fishing safety Oct. 14, 2021, Dzugan talked about the other, long-term positive changes he’s seen.

“There has been a sea change in the attitude of fishermen compared to 30 or 40 years ago when I started fishing,” Dzugan told the group. “It has not been a revolution.”

There is greater acceptance of the need to spend money and time on equipment and training, but training sessions show there is still a strong need for education, he said.

Fishermen “score about 60 percent before the test on simple basic items” about safety knowledge, Dzugan said. “So there’s something like a 30 percent basic shortfall.” After training and final testing, scores come up to 90 percent and better, he added.

“Jerry, we’re in a flat spot when it comes to reducing” vessel casualties, said Morgan Turrell director of NTSB’s Office of Marine Safety.

Dzugan responded that the Coast Guard should use more of its existing authority for checking vessels. He said one good example had been new efforts in Alaska to check and weigh crab pots — which is showing the gear often is heavier than expected, with all the implications for vessel stability.

It has been more than 40 years since Dzugan left the classroom, to now advising federal safety agencies. Even at the start, there was a fishing connection.

Back in Chicago in 1979, Dzugan had told his department chairman, Earl Jeffrey, of the decision to move north. Dzugan was astonished when Jeffrey told him Sitka was a good place. Jeffrey had worked in Alaska, fishing during his college years, and gave him the name of a Native Alaskan captain, Moe Johnson, he had fished with and knew well.

“I put that in my hip pocket and thought, ‘I’m going to look this guy up when I get there,’” Dzugan recalled.

In May 1979 Dzugan and his BMW motorcycle, “my prized possession,” arrived in Sitka. Soon he was making connections, walking the docks, and then fishing. The first fisherman he met was Moe Johnson.

Years later AMSEA was holding three-day kids’ fishing safety workshops for teachers from Native villages, when Dzugan got a call from a teacher on Prince of Wales Island asking about the program. He asked the man’s name.

“It’s Earl Jeffrey,” the teacher said.

“Wow, that’s such a coincidence, that was my former department chairman in Chicago.”

“I know. I’m his son… I know all about you.”

The younger Jeffrey told Dzugan how his father had gone right to work in the Chicago school system after college to support his family, “and his dream was always to be in Alaska.”

“I said, ‘You’re living your father’s dream.’”

“Exactly.”

And now, Dzugan added, “his father comes up every year.”