“The disadvantages of being a lobsterman” by T.M. Prudden

Part two: “The advantages of being a lobsterman”

Featured in the July 1963 National Fisherman combined with Maine Coast Fisherman issue.

It is primarily concerned with the lobster fisherman. Still, it dwells on the other sides of the lobster industry, such as the lobster buyer, the business of pounding lobsters, and the wholesaler.

Lobstering is a big business, big beyond what most people realize, both in quantity and in dollar value. The average catch in Maine is approximately 25 million pounds, worth around $10 million. Maine is the state that catches the largest number of lobsters; Massachusetts is next, but its catch is only about one-sixth that of Maine.

It is natural that any boy (or girl, for that matter, and there are several successful lobsterwomen) who live near the sea may turn to lobstering for his lifework. But it is a different sort of life than most people experience. It can be a good life and a profitable one. IF

If you can stand its loneliness.

A lobsterman is up before dawn and is usually alone during his fishing. It is surprising how few lobster boats are equipped with radios whose music would ease the monotony, as they do in factories. Sure, some fishermen with many traps (perhaps up to 200 or even more) have company and take along a helper if they plan to haul the whole string every day. But this is an overhead expense and can be the bane of a lobsterman as it is in any other industry. It divides the profit, though the increased catch may compensate for the loss.

The man whose interests are centered on things outside himself (the extrovert) may be less happy than the man who finds his satisfaction with his own inner thoughts (the introvert). But there is no such thing as being wholly introverted or wholly extroverted. All of us have some of each characteristic. However, once a lobsterman has reached his fishing grounds, he is busy and has little time for daydreaming.

Can you do without company while you are working?

If you will realize that it is a poorly paid profession.

Or, more precisely, it is poorly paid for the majority, who could probably earn a better day’s pay working for Bath Iron Works. But this shipyard is not nearby for most men, nor does such supervised and confining work appeal to those with an independent streak—they have got to feel free and be their own boss.

There are over 5000 registered lobstermen in Maine alone, and they catch approximately 25,000,000 pounds of lobster per year. That averages out to 5000 pounds of lobsters per man. It includes the little man with only 20 pots fishing from a dory as well as the expert who catches more than average.

Yet, 5000 pounds per man in a year, at a price of 50 cents per pound, only comes to $2500 per year, and out of this must come the cost of bait, gasoline, and gear maintenance (30% loss of pots per season is not uncommon).

You must be determined to be a topliner if you want to earn a good living as a lobsterman. Education is the probable answer.

Lobstering does not have to be poorly paid and isn’t for a few topliners. It isn’t easy to discover what makes one lobsterman much more successful than another, any more than you can put your finger on one doctor’s success versus another doctor. His knowledge of his art (skill) is probably an outstanding requisite.

Notice that hard work is not listed here because most lobstermen are hard workers. Good luck seems to be of small influence since a bad storm and lost gear can hurt the expert lobsterman as badly as the dub, though perhaps the expert will read the signs of an approaching gale and get some of his pots ashore.

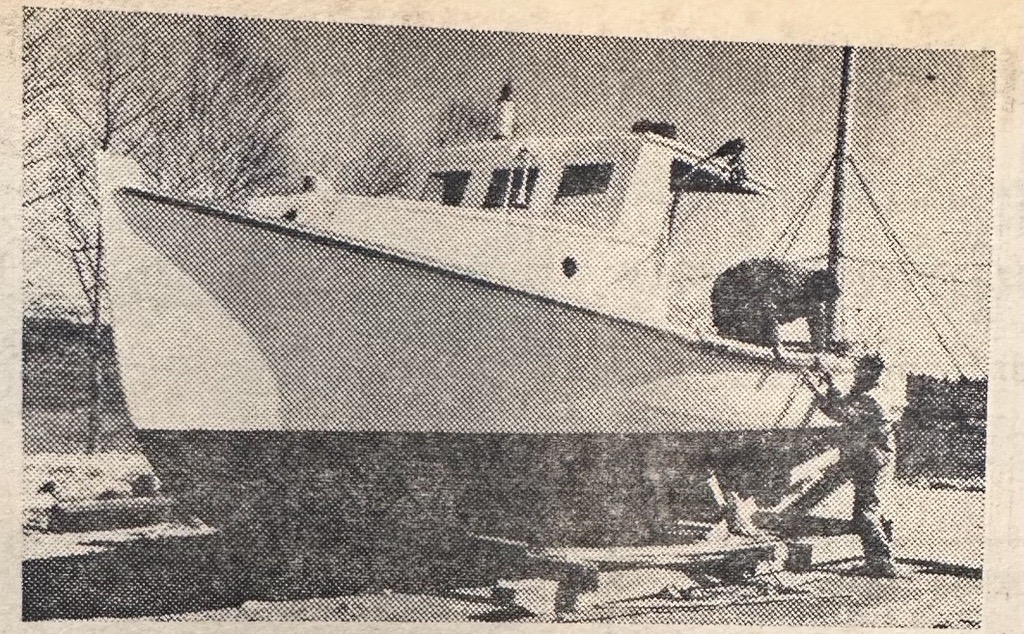

Back to the sea again is Billy Plummer's plan from Five Islands, ME. Shown with Ben Backman working on this 29’ lobster boat. Bill has been running a general store at Five Islands for the past two years, but before that, he lobstered with Arthur Tibbetts of Bay Point, and the call to return has been too strong. Billy plans to fish about 300 trap pots out of Five Islands. Photo by Owens

The Key

If knowledge is the key to becoming an outstanding fisherman, then what must this man know, and how can he acquire the education?

In the first place, the young fisherman must want to know more about lobsters. If he isn’t smarter than lobsters in learning their habits and appetites, he will not become a topliner. It sounds easy, doesn’t it? But it is not.

There are countless lobstermen who have fished all their lives. They rarely question the effectiveness of their gear or will listen to suggestions. They are much ruffled at the idea that anyone outside their trade can tell them anything.

It is education that is lacking (not book-learning education but education in their trade), and it is pretty hard to teach an old dog new tricks.

Education can start by apprenticing yourself to an experienced lobsterman for a season. He should be a successful fisherman, but above all, he should be a man who will share his knowledge, i.e., how does he know that it is good fishing ground at Jones’ Point in August but not in June, and why is he changing bait from redfish to herring? And if he is a topliner, notice how poorer lobsterman drop their pots around his set and how they fumble around to find his new fishing grounds when he moves- always following, not leading.

Suppose you set your heart to being more than an average lobsterman. Are you prepared to learn and keep on learning from any source, even the summer visitor (who may be a distinguished developer of new ideas) who innocently asks, “Why don’t you start lobstering later in the morning instead of at the crack of dawn?”

Most lobstermen wouldn’t bother to answer this question and would glare at this questioner in stony-eyed contempt. But a man who is continually searching for education will think, “That’s a thought. Are our reasons good enough today?”

Unfortunately, the solitariness of a lobsterman’s life and the rareness of his contact with people outside his own small community very limit his knowledge of what other men are doing. It must, and it does, result in narrow-mindedness. You laugh if a neighbor says, “My father lobstered for 50 years. He knew where the ledged and feeding grounds were. What is good enough for him is good enough for me.”

Yet will you turn up your nose at equipping with a depth recorder, calling it new-fangled, unnecessary, and sissy fishing gear? The ledges don’t shift, but your memory may. Or will you try out a new pot design if it is offered to you?

Education is probably the greatest need for the whole lobster industry. Very few lobstermen will recognize this. They are so close to their job, and so steeped in their habits that they can’t or won’t draw off and size up the whole picture.

Are you ready and capable of doing this? The topliner is able to see his weaknesses, which is the first step towards correcting them.

You may doubt the statement that many lobstermen are closeminded but consider today’s lobster pots. It hasn’t changed in over 100 years except for the addition of the parlor. How many other tools haven’t been improved in 100 years, except the lobster pot?

Even the frying pan is less clumsy and less greasy, and the how is of better steel and lighter. Has the number of men required to catch 1000 pounds of lobsters been appreciably reduced?

Pots are still made of wood and become lighter when immersed in seawater when they should become heavier to anchor them to the sea floor. They still will allow trapped lobsters to escape. They still can be smashed and rolled about the ocean floor in a storm. They still are being chewed up by teredo. Is it advancement?

Advancement of lobstering practices will have to come from today’s apprentices, at least from those who see the need for educating themselves and will seek the education.

Open-mindedness is the opposite of narrow-mindedness. Will you try anything which promises to benefit your trade? Lots of fishermen won’t be bothered.

It has been said, “The very first essential of any real education is to observe concrete facts. Unless you do this, you have no material out of which to manufacture knowledge. Compare the facts you have observed, and you will find yourself coming to conclusions. These conclusions are real knowledge, and they are your own.”

Education includes testing the truth of many accepted practices and weeding out “old wives’ tales.” Some lobstermen insisted on using dyed-green nylon twine for their pot heads. Others insist that only brown or white are effective. Do you believe there is any difference? There may be, but no scientific tests have been published to prove the point. Or are these beliefs just “sot-ness”?

On the other hand, there are many beliefs of lobstermen which are true and which have been proven over years of use, but it is surprising the number of practices which are effective but to which the lobstermen attribute the wrong reasons.

The new oak trap won’t fish until it has been soaked for a week in seawater to “make it waterlogged.” Of course, it will soak up water in a week, but it is more likely that it is the acid leaching out of the oak that makes it fishable.

Experience Needed

To be sure, the brash young beginner must learn that there are “know-hows” of the old timers that can’t be overlooked. For example, a young engineer fresh out of college had learned to accurately measure the heat of a flame with a pyrometer. Then he sees the village blacksmith haul a white-hot piece of iron out of his fire, hold it up to squint at it, and declare, “That’s just about hot enough.” The young engineer is aghast at such slipshod methods of judging heat.

However, as he grows older and more experienced, he is surprised to learn how accurate the blacksmith’s judgment is. Years of experience with glowing iron have given him knowledge beyond the understanding of the untaught. An old-time lobsterman has learned similar valuable ways of judging.

There are several college graduates who are lobstermen, and they are highly successful. In talking with them one is impressed that their success is in no way due to their “book learning” but in the training of their minds to question the accepted means and gear for fishing, and their willingness to study the lobster and outsmart him.

If you can stand the rugged life.

Lobstering is a rugged life. The summer visitors see a lobsterman hauling his pots on a warm summer day with little wind and no sea running. It looks to be an ideal way of earning a living.

But let this same visitor get up before dawn, lug aboard three bushels of stinking fish bait with five gallons of gas, and row them out to this vessel. It may be raining and blowing smart. The sea will be rough, and it will be penetratingly cold.

As soon as he has passed the lee of the harbor, the visitor will be seasick and, oh, so miserable and glad to take shelter in the cuddy. The lobsterman may not be seasick, but he can be miserable too, and he’s got to continue most of the day and darned glad to creep home to a quiet harbor.

Multiply these miseries for fishing in the colder weather of early spring and late fall, and you test a lobsterman’s ruggedness.

Then consider the man who fishes all winter. He probably doesn’t put out oftener than every other day but that is no job for a weakling. Can your hands stand being continuously wet with 40-degree water even though you wear cotton gloves? Yet it pays, for the scarcity of lobsters in the winter nearly doubles the price for your catch.

If you have the heart to meet discouragement.

Imagine it, all day out in the cold and only 10 lobsters to show for it- not enough to pay for your gas. You shift the location of your pots, you change your bait and still no decent catch all week- the lobsters just aren’t feeding.

Then you run into a three-day nor’easter when you can’t go out. After the sea calms down, you spend two days just hunting for lost pots (at $3 a pot). Some of them will be lost for good, having been rolled over and over by the waves, thus winding the warps around the body of the traps and drawing the buoys down out of sight. Others will have been shifted by the waves, and you will zigzag back and forth over the sea searching for them. You will wearily put for home with a deck load of smashed pots to be repaired when you are next stormbound. Up to 30% of a man’s pots are lost each year.

Is your courage strong enough to stand this and look beyond to see that is the average results that count, not just the days of hard luck?

Or take the period of good weather when lobsters are plentiful, and your catch is good. It is very heartening- until you sell your catch and find the price is 15 cents a pound less than it was yesterday- for there is a glut of lobsters.

Maybe you say, “This is a hell of a business,” or maybe you get mad at your buyer and shift to another buyer who offers a quarter-cent more per pound.

The topliner will rarely do either of the things. He knows that supply governs demands (and prices), and the dealer shouldn’t be blamed. He also knows it doesn’t pay to get mad with his buyer, for the lobsterman who isn’t loyal to his buyer won’t find the buyer loyal to him and willing to take his catch when the buyer is already loaded up.

It is hard to imagine greater narrow-mindedness than of a fisherman who has been buying gear from his buyer on credit all winter, yet who shifts from this buyer during the catching season because someone else offers him a quarter of a cent more. It happens.

If your home port is a good enough location.

If you live on a harbor which supports 200 lobstermen but only two buyers, you are in the hands of those buyers and they can be as arrogant as they please. But if there are more buyers, you can pick the one who treats you best year in and year out.

Of course, it may be necessary to switch buyers, but the topliners do this infrequently. A man with a record of often changing jobs is a poor bet for any employers, and so is the lobsterman who often changes his agent.

It is not easy to pull up stakes and move to another port, but it is better to state under the best conditions, for once you have learned your fishing grounds, it will be a hard job to locate the best reefs, etc., out from another port.

Another consideration is the number of lobstermen fishing out of your port. There are too many lobstermen in Maine as it is; there are so many that only a few can earn a decent living. And there are only so many lobsters to be caught.

So, if there are two lobstermen for each lobster caught, there is little profit in fishing out of your home port. Educate yourself on what harbors are most promising. If you write to Augusta, the Department of Sea and Shore Fisheries can help you (not just the wardens; they know only one section of the coast).

Two other factors to investigate:

Can spare parts for your motor be procured nearby? Is there a dependable source of bait?

Next: The advantages of being a lobsterman.