Setting sail towards the future, Arctic Storm Group is introducing its 99-meter vessel, the Arctic Fjord, to the challenging waters of the Bering Sea. This technologically advanced vessel is a testament to our commitment to innovation and competitiveness.

In 2015, as Russia embarked on a multi-billion-dollar program to modernize its Bering Sea fleet, the Forward-thinking Arctic Storm Management Group seized the opportunity to build a 99-meter catcher processor vessel, the Arctic Fjord. “Our aim was to create a vessel that would remain highly competitive even a decade from now,” emphasized Arctic Storm’s vice president, Brett Johnson, underlining the company's strategic foresight.

It has been said that fishing vessels are among the most difficult to design and build because of the number of dynamic variables involved, such as power consumption, stability considerations, and many others, particularly in the case of a processing vessel.

“We designed it with Kongsberg-Rolls Royce,” said Johnson. “Rolf Barstad made the vessel fit our needs. Carsoe modeled the factory with us,” Johnson added, referring to the Danish onboard processing equipment and systems company.

“We started the design in 2016,” said Rolf Barstad, of Kongsberg. “The bow is different; it’s made to cut through the waves, and we optimized the hull for fuel consumption. We did a 3D computer model of the hull, tested it with CFD [computational fluid dynamics], and made changes. SINTEF Ocean built a model according to our lines and tested it in Trondheim's Norwegian University of Science and Technology flow tanks. They made a report, which was also sent to Arctic Storm Management Group. During the work on the specifications, we needed to calculate electrical power, fuel, water, heating, etc. Everything that was needed on the ship.”

During the design phase, Kongsberg worked closely with suppliers of the equipment required for the ship. “This means a lot of work and changes in the design as well as new solutions for the equipment to fit in,” said Barstad.

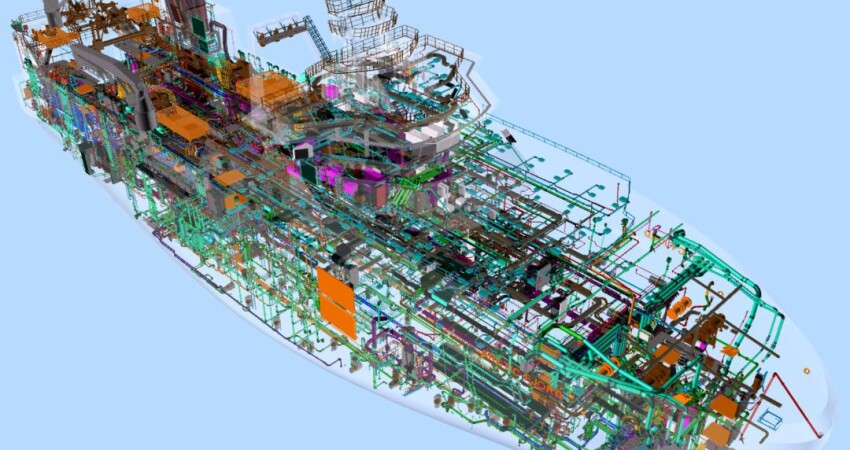

With the hull shape established, general arrangements and specifications finished, the price set, and a yard found, Kongsberg started to make the DNV classification and arrangement drawings. Barstad noted that Navis, a Croatian-based Kongsberg Maritime company, produced all the detailed drawings and cut files for the steel. “They also made a detailed 3D model of the ship,” he shared. “For their own purpose and for the owners to investigate to see if they wanted to make some changes.”

Barstad noted that stability calculations were important during the design and construction phase and were constantly adjusted. “For the stability and trim calculation, we looked at conditions from 10 percent fuel and no catch—the lightest—to a full cargo and full fuel,” Barstad said. “We tested stability in the computer and made rules for the captain of how to move cargo, fuel, and water ballast to maintain stability.”

After two years of planning, Thoma-Sea Marine Constructors LLC laid the keel for the Arctic Fjord in 2018. “We cut the first steel in October of that year,” said Brett Johnson on Arctic Storm Management Group. “We had some things we wanted, but we’re fishermen, not boat builders, so we had Crowley Marine oversee the building,” said Brett Johnson. “They reviewed the drawing with us and had three guys, including their structural guy, on-site all through Covid, which was really fortunate.”

“Don’t let anyone fool you. We can build molded steel in the U.S.,” said Johnson, “We went over to Holland to talk to a company there, Central Stahl, that cuts and bends the plate for molded hulls, but they did not want to work with a U.S. yard. Walter said he could do it, and he did more than 90 percent of it. Only some pieces, like the nozzle for the bow thruster, which was 2 inches thick, had to be sent out to a company in Texas. But 100% of it was formed right here in the U.S.”

According to Johnson, Thoma-Sea tooled up to build the Arctic Fjord. “Walter Thomassie bought a 400-ton Faccin press to bend the T-frames and European-style bulb flats. We’re not using angle-iron stiffeners. With the bulb flats, they bend the port and starboard side stiffeners on top of each other so that they are mirror images.”

At the Thoma-Sea yards in Houma and Lockport, a combined crew of over 400 started building the hull sections. “About 30 percent of the modules were built in Lockport,” said company owner Walter Thomassie. “It’s about four hours away by barge. We would load the modules on the barge in the morning and take them off in the afternoon. Usually, the last one would go right on the boat.”

Building a boat in modules at separate locations and putting them together into a fair hull requires precision, and Thomassie credits his team, particularly the quality control guys. “It’s what comes out of the shop that makes a difference. If the module is built right, it makes everything else much easier,” he said, noting that they use several tools to keep measurements precise, including lasers and transits. “And we use good old piano wire—old-school,” he said. “It’s not the tool as much as the skill of the guy using it.” In the first 90 days of work, Thomassie noted that the yard put together 17 modules. “Those first four or five sections each took 18 hours to put together.”

As the hull took shape, the guts started to go in, including the 9,655-hp Bergen 33-45 12V main and all the systems from freezing to heating to handling gear and the needs of 152 people. “What makes these vessels so complex is the density and layers of systems that have to go into them,” said Thomassie. “You’ve got your propulsion and auxiliary power. Then you’re going to process surimi, fillets, fish meal, and oil. You need to make water, and you need to freeze 250 metric tons of fish daily. Then, there is the fact that there are 150 people on board. You must feed them; you need gray water and black water systems.” The list went on and included the vessel’s heating system for urea used in exhaust after-treatment and heating forward to reduce ice accumulation.

“They had a massive heat recovery system,” said Thomassie. “From the water jackets of all the engines and the exhaust, and if they’re idling, there’s a boiler. The piping is so dense that if you took the shell off the boat, you could still see the shape of it just from the pipes. There’s a lot of work there. I give credit to the designers and the team at Arctic Storm.”

Thomassie pointed out that while building started off according to plan, production slowed in the face of COVID in 2020, and Hurricane Ida in 2021. “We needed Brett’s expertise, but he was on lockdown and never came to the yard for 14 months. So, we had weekly meetings online with him and the Arctic Storm guys.” The yards at Houma and Lockport also had to deal with an unstable workforce and new ways of operating. “We had to think about how to move people around and isolate groups.” Then in 2021 as COVID concerns diminished, Hurricane Ida struck, damaging the town, and wiping out the surrounding infrastructure, though the boat remained undamaged.

Then, supply chain issues kicked in. “People weren’t restocking because the world had stopped,” shared Thomassie. “And so, things that you could get in two weeks became 12 weeks, six months, a year. So that affected planning.”

As the world started turning again, contractors returned online and installed the factory, the electronics, and other specialized systems. Arctic Storm took delivery of the Arctic Fjord in Houma in July 2023, and took the new vessel through the Panama Canal and on to Seattle late that month.

All photo courtesy of Arctic Storm