Look out at the radars atop the wheelhouses in almost any fishing port in the United States and Canada, and one name stands out — Furuno. The company’s blue-on-white logo is visible on the domes and open arrays of vessel after vessel.

According to Eric Kunz, senior product manager at Furuno USA, customers are seeing huge leaps in radar technology. Since World War II, Kunz says, radar has relied on the magnetron, a high-powered vacuum tube that works as a self-excited microwave oscillator. Crossed electron and magnetic fields are used in the magnetron to produce the high-power output required in radar equipment.

As Kunz tells the story, the British developed an innovative magnetron early in 1940, but concerned it might fall into German hands, they sent it to the United States in exchange for aid.

“They sent it to MIT, where it was used to develop the first radar, and then RCA and Bell started mass producing it. They used it to spot U-boats, and it helped us win the war of the North Atlantic.”

But after 80 years as the foundation of radar, things are finally beginning to change. “Since 2018 we’ve been delivering NXT radars,” says Kunz. “These are not your traditional magnetron radars. They are solid state, with transistors and digital signal processing.”

Kunz explains that while the magnetron enables radar to collect information on range and bearing, the solid-state technology provides a third piece of information — radial velocity, or Doppler.

“With Doppler,” Kunz says, “you can see if a target is coming at you. And if it’s coming at more than 3 knots, the radar turns it red, tracks it and gives you its CPA, its closest point of approach.”

Among other features, Kunz highlights Furuno’s rain mode on some radars. “Solid state allows us to look at the signal quality, and our target analyzer can differentiate targets from rain. This is all developed by us.”

Kunz goes out on fishing boats and talks to fishermen about what they want. “What a lot of fisherman like is our True Target Trails. A heading sensor in the satellite compass is integrated with the radar to give true radar trails so that they can see at a glance what is moving in relation to them. If they have an AIS overlay, they can find out what kind of vessel it is and where it’s going.” Kunz notes that besides collision avoidance, True Trails can give fishermen an idea of what other fishing boats are doing. “Some use it that way,” he says.

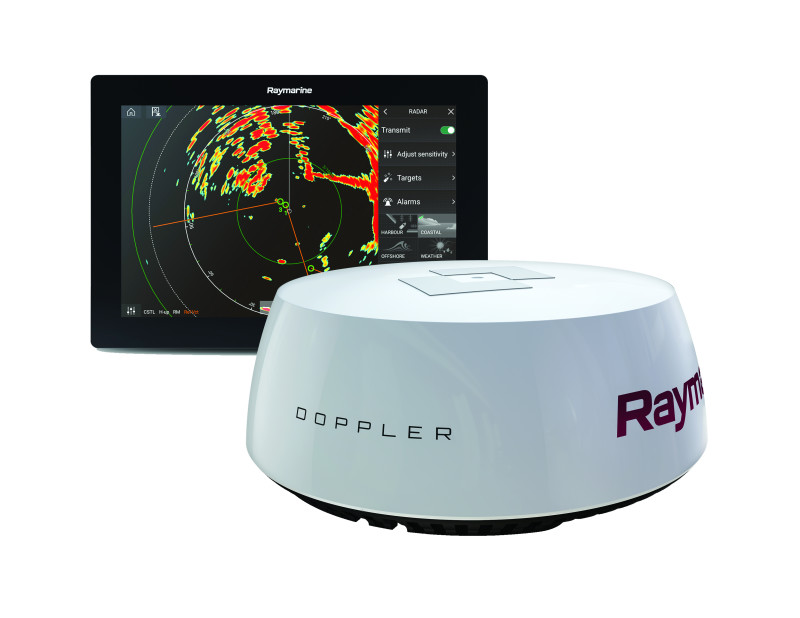

Long a favorite of the recreational fishing and yacht communities because of its very user-friendly platforms, Raymarine has been making its way onto commercial fishing boats.

“The Northeast is our biggest slice,” says Jim McGowan, Raymarine’s maritime marketing manager for the Americas. “Of course, we have the home field advantage being here in New Hampshire. Mostly we sell to lobster boats and smaller trawlers.” According to McGowan, Raymarine has two radar systems that could have commercial fishing applications, the Magnum and the Quantum.

The Magnum has an open array 4- to 6-foot antenna, and while using a traditional magnetron transmitter, the information is processed digitally. “The 6-foot antenna Magnum can pick up targets as far away as 96 miles,” says McGowan, adding that it can track weather and large vessels, and flocks of birds. “The birds show up blueish green, and a lot of times can indicate the presence of baitfish. And you know, where there’s feed, there’s fish. Radar used to be collision avoidance and navigation, but now it’s more of a fishing tool.”

Raymarine also makes a solid-state Quantum radar system, which has a 22-inch dome antenna, but like the Magnum, is ARPA (automatic radar positioning aid) compatible.

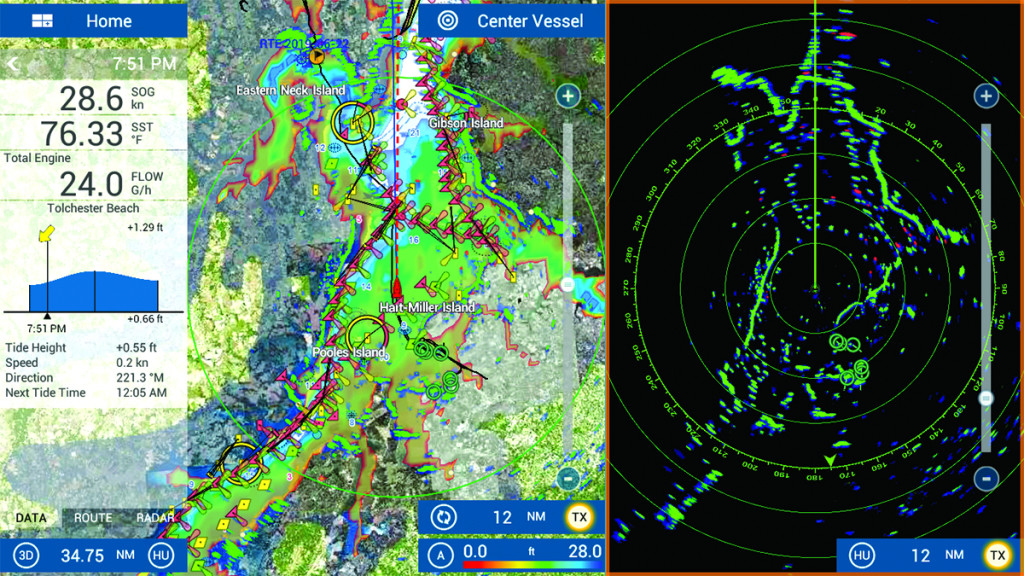

“The Quantum has a CHIRP pulse that provides fine detail,” says McGowan. “It uses Doppler to track moving targets. It’s great if you are pulling traps in the fog, especially in high-traffic areas like Boston Harbor.” With Quantum, McGowen notes, the targets are color coded so users can see at a glance what’s happening around them. “Oncoming targets show up red, and receding targets are green,” he says. “ARPA plots the targets. It can lock onto them and track them, and you have visual and audio alarms.”

Both systems can be set up with Raymarine’s Axiom multifunction display or used through apps on a cellphone. “Our products are easy and intuitive,” says McGowan. “Nobody wants to read a 500-page manual. You can download the apps and have everything on your phone, and you can check it even when you’re on deck.”

McGowan points out that Raymarine also provides equipment for the Coast Guard and the Navy. “We build to military specs,” he says. “Our equipment will withstand salt, shock, and vibration.”

JRC, a Japanese marine electronics company, has its U.S. headquarters in Houston. JRC designs and builds similar products to those of other manufactures in the marine industry.

“What we offer is durability and support,” says Ramon Rodriguez, strategic account manager for JRC. “We have been manufacturing maritime products for over 100 years. When a system is discontinued or replaced, we will continue to support the product for a minimum of 10 years.”

Rodriguez notes that the company’s commercial fishing market, with many sales in the Pacific fleet and Alaska, is expanding into the Canadian maritime industry. “We have many products that fishermen like,” he says. “The JMA-3400 series can be set up as an X-Band or an S-Band radar with different configurations and options available. The JMA-3300 series with a 10-inch display, the JMA-3400 series with a 12-inch display, or the JMR 5400 series with a 19- or 26-inch display. These radar displays can be connected to a variety of different antennas. The JMR-5460 is a 60-kW high-power S-band radar for bird detection. It can detect birds 80-90 miles away with the 8-foot open array antenna.”

Rodriguez notes that the JRC JMA-3400 displays have a USB port for a mouse and can import C-Map Max charts. “You can put your chart on the screen,” says Rodriguez. “And the radar gives your position in relation to the chart when a GPS is connected to the system. The JRC GPS antenna can be connected directly to the radar processor removing the need for extra equipment and wiring.”

According to Rodriguez, JRC’s solid state S-band radar, the JMR-5400 series, can track even the smallest targets, and can pick up floats on seines and gillnets. “We sell a lot to the Pacific tuna boats,” he says, noting that in addition to use in spotting distant birds, it is valuable when boats are working in close proximity to each other.

Among the bigger names in radar, 73-year-old Koden Electronics is the only one yet to introduce solid-state transmitters.

“All of the Koden radars we sell are still using magnetrons,” says Brian Sibley, the Mackay Marine sales manager for the Canadian Maritimes. Sibley notes that Koden can get a commercial fishing grade radar onto a 45- to 80-foot boat for as low as $3,000 U.S. dollars.

“Most of the equipment we sell is to the large inshore fishing fleet,” says Sibley. “A lot of companies have gone to complexity, and menu-driven touch screens, but Koden has kept things traditional, with commercial fishermen in mind. There are still knobs and direct pushbuttons on the machine for the customers who want something simple.” Sibley notes that many Koden units are repairable if they fail. “With a lot of systems today, replacing the unit is the more viable option if there is a failure.” he says.

While Koden sells dome and open array antennas, Sibley leans toward selling the open array. “If you’re trying to spot a high-flyer, even a small 3.5-foot open array will give you a better chance to see it. The dome radars are for the smaller fishing boats that need a decent inexpensive shorter range radar, a backup radar, or a radar when the fog rolls in, so they can keep fishing.”

But for those comfortable with computers onboard, Koden is coming out with a new black box radar interface. “With the black box interface, the radar array plugs into a processor, and you can feed that out to a PC with software. You can also get a stand-alone black box radar that outputs direct to a computer screen. A lot of younger fishermen like that because you can get a much larger screen for the cost. In the past, black box products have been very expensive, and many manufacturers have moved away from them. Koden is now able to offer something for that market.

According to Gerry Splitt, territory manager for Navico, which owns four marine electronics brands, including Simrad and Lowrance, magnetron systems are not going away. “We still have magnetron systems,” says Splitt. “Our R5000and Argus Radars are commercial systems that are IMO approved.”

But Navico is also big into solid state, and its broad market is helping drive its research and development. “We’ve upgraded from our 3G and 4G broadband transmitters to pulse compression technology that works well in small boats for smaller targets and boats working close together,” says Splitt. “Our radar gives out one pulse that contains five chirps, smaller pulses at different frequencies that it stitches back together to make a single image on your display.”

According to Splitt, the Simrad Halo radars can accomplish this with 150-watt (peak) at maximum wind velocity, 40-watt (average) at zero wind velocity, of power. “A typical radar is going to have a 4-kW to 30-kW signal. We’re matching a 6-kW magnetron radar and doing it with the same energy as a light bulb.”

The Halo has its versions of the bells and whistles its competitors have — Doppler tracking capacity and different modes for different conditions. What Splitt is excited about is what these radars offer in terms of performance for the price. Splitt describes a test of the Simrad Halo against a comparable commercial radar, both 35 feet up. He admits that the Halo tracked a target to 11.2 miles, to the competitor’s 11.8. “But ours costs $6,499, and the competitor costs $100,000. If you don’t mind giving up half a mile, I’ll save you $93,000.”

While a vacuum tube that helped win a war has been an integral part of the radar world for 80 years and counting, as Raymarine’s Jim McGowan says, solid state technology and other innovations are making radar more of a tool for fishing.